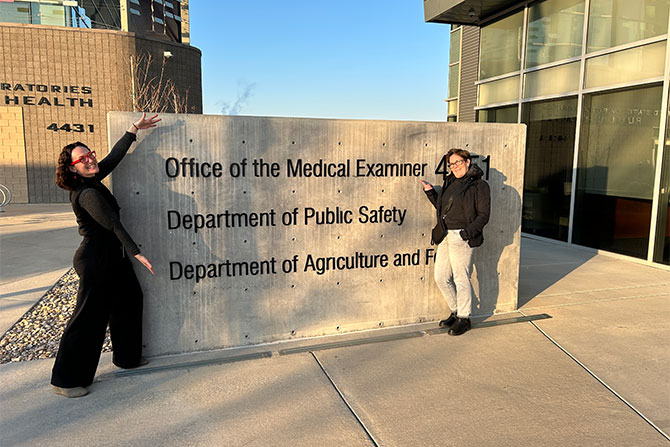

Feature image: Dr. Deirdre Amaro and UAFP CEO Maryann Martindale outside of the Office of the Medical Examiner after a tour of the facility.

When Deirdre Amaro, MD, walked into her first autopsy as a medical student, she didn’t expect to feel wonder. The case was messy, quite literally. A bowel perforation during evisceration and holding a human brain for the first time did not inspire revulsion as it might in some. “This is so freaking cool,” she remembers thinking then, and still thinks now as Utah’s chief medical examiner.

Amaro didn’t set out to become a forensic pathologist. She began medical school with a vision of pediatrics as a career, but the pace of outpatient visits, the brief time she had to meet with them and the sorrow of inpatient pediatrics nudged her toward pathology. She completed a forensic pathology fellowship in New Mexico, followed by a neuropathology fellowship (“I’m prepared for the zombie apocalypse,” she jokes). She spent the next leg of her career as a sole practitioner for a sheriff’s office in far Northern California.

Eventually, she decided she missed academia and took a position in Missouri, initially as an assistant medical examiner and later as the chief medical examiner. While there, she also joined the faculty at the University of Missouri in the pathology department. When asked what brought her to Utah to work as the chief medical examiner for the Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS), she, like many, mentions the beauty of the mountains, as well as the relative lack of ticks and summer humidity prevalent in Missouri.

Another benefit of working in this capacity in Utah is the Office of the Medical Examiner’s (OME) statewide structure. Much of the U.S. is a patchwork of death investigation systems; most jurisdictions are county-based, and many are led by elected coroners with varying levels of training. In some places, the qualifications to be a coroner amount to age, residency and winning an election. Autopsies may be performed by “any willing physician” in many jurisdictions.

Utah, by contrast, runs a statewide medical examiner system within the DHHS, which establishes uniform standards and ensures consistent data collection. It also, crucially, provides a direct link between death investigation and public health. “People think a death certificate is just paperwork,” Amaro says. “But the cause and manner we assign are coded into ICD. That becomes mortality data. It’s how we know what’s really killing people — and how we decide what to do about it.”

She can point to the benefit of this data for public health, both contemporary and historic. In the present, Utah’s clarity about fentanyl-related deaths through robust and accurate data has underpinned a multi-stakeholder response, including the governor’s Fentanyl Task Force. A historical example involves an autopsy technician on the East Coast who noticed an alarming pattern: infants dying in car crashes at far higher rates than others. Once validated with national mortality data, that observation helped drive a change in car-seat requirements, which led to a decrease in the number of infant deaths in car accidents. Cases like these illustrate the profound impact that the quiet, meticulous work of death investigation and data analysis can have on the lives of the living.

For family physicians, the most immediate intersection with Amaro’s office is the death certificate. Most deaths in Utah are natural deaths under physician care and never become ME jurisdiction. That’s where clinicians often feel a pang of uncertainty. The patient died at home over the weekend. Police arrived first. The funeral home is calling. What now?

First, Amaro reassures, it is typically unnecessary to complete a certificate outside business hours. While issuing the death certificate promptly is critical for the family of the deceased, it’s normal for physicians to take time, gather the information they need to complete the certificate and ask for help from the ME if needed. “There are several steps that happen before your signature is needed,” she says.

Law enforcement often makes the initial scene assessment in unattended deaths; the funeral home usually coordinates the next steps and outreach to the treating physician. If the scene investigation has ruled out trauma, overdose or suspicious circumstances, and the patient’s clinical history supports a natural process, it may be reasonable to certify a natural death even without an autopsy. “Uncertainty is part of medicine,” she notes. “An autopsy isn’t a magic box that always yields a single, definitive answer. We make clinical judgments in life; we also make them at the end of life.”

If families ask about an autopsy outside the ME jurisdiction, the pathway is a hospital or private autopsy. Both require consent from the legal next of kin. Utah has an additional safeguard that clinicians should be aware of and explain to families: The ME’s office reviews every case slated for cremation or removal from the state. Most reviews are straightforward, but they occasionally surface concerns that warrant a deeper look. “Sometimes the body is the evidence,” Amaro says. When that evidence would otherwise be destroyed or leave the state, the office may intervene — a necessary step, though it may be inconvenient for families.

Behind these processes lies Amaro’s larger appeal to family physicians: collaboration. Physicians receive little formal training in death certification. It can be stressful when a patient dies and the “final diagnosis” falls to a clinician who wasn’t present at the time of death and, in some cases, has not seen the patient in some time. Her message is simple: Call us. “If one of your patients dies and it’s not our jurisdiction, but you have questions about how to structure the certificate, we’re happy to help. We know how important this is for the family, and for understanding the health of our community.”

That collaboration begins with a shared ethos. To Amaro, signing a death certificate is an act of care, not a bureaucratic chore. It honors the patient’s story with a clear, defensible conclusion that reflects what we know about their health and the circumstances of death.

When uncertainty creeps in, consider the information you, as the physician, obtain because of a competent scene investigation: no evidence of trauma; medications accounted for; no red flags for overdose; no indicators of foul play. If those things are ruled out, a natural death grounded in known disease is the likely culprit. And if you’re still uneasy, pick up the phone. The point, Amaro stresses, is not to impose decisions on busy clinicians, but to stand alongside them.

Utah’s system isn’t perfect, she admits. No system is. Even here, late course corrections occur: a cremation review triggers a deeper inquiry; a case that should have come in earlier is retrieved; plans are disrupted. But the redundancies are purposeful, designed to protect families and the public’s trust. In her view, the difference lies in a culture that prioritizes accuracy and cooperation over speed or convenience.

Ultimately, the work proves surprisingly humane. Families arrive at the ME’s doorstep, stunned by loss and overwhelmed by the logistics of death, including the funeral home arrangements, the paperwork and the toll of grief. “The business of death adds an extra layer of trauma,” Amaro says. “If we [the ME’s office and clinicians] can minimize that through education, partnership and timely certification, everybody is better served.”