The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines state:

An estimated 20% of patients presenting to physician offices with non-cancer pain symptoms or pain-related diagnoses (including acute and chronic pain) receive an opioid prescription. Chronic pain has been variably defined but is defined within this guideline as pain that typically lasts more than three months or past the time of normal tissue healing. Chronic pain can be the result of an underlying medical disease or condition, injury, medical treatment or condition, injury, medical treatment, inflammation, or an unknown cause.

Physicians report multiple barriers to appropriately managing chronic pain, including lack of time, training, increased scrutiny on opioid prescribing, and fear of patients developing opioid use disorder. In addition to these concerns, several studies have reported increased physician burnout in the management of chronic pain from a lack of patient self-management skills. From Carole Upshur, EdD, and colleagues in “Primary Care Provider Concerns about Management of Chronic Pain in Community Clinic Populations”:

“Despite the unfavorable reports about pain education and low satisfaction with pain treatment, PCPs did not identify provider expertise and health system factors (e.g., difficulty of diagnosis, lack of evidence-based guidelines) as the most important obstacles to treating patients with chronic pain. Instead, patient compliance and behavioral factors were rated as more problematic.”

Using a systematic evaluation in chronic pain management, including implementing the resources found in the American Academy of Family Physician’s (AAFP) chronic pain management toolkit, allows for physical, mental, and functional evaluation of patients who suffer from chronic pain. After completing a thorough evaluation, a physician can determine appropriate medication and additional treatments and therapies that can be taken to improve self-management skills.

In March 2014, AAFP launched the Chronic Pain Toolkit, giving physicians multiple resources in one location that are easily accessed and downloaded.

The Chronic Pain Toolkit is divided into five sections:

- Pain Assessment gives an overview of appropriate strategies and diagnostic tools used to support chronic pain assessment in patients.

- Functional and Other Assessments discuss supporting tools and methods for the diagnostic assessment of functional activity and other coexisting conditions, including the patient’s emotional and mental health, quality of life, and other psychosocial factors.

- Pain Management provides details on strategies and considerations for effective management of acute and chronic pain.

- Opioid Prescribing covers the prescribing of opioids as it relates to the treatment of chronic pain and includes information and resources on safe prescribing practices, risk mitigation and monitoring, opioid conversion and tapering tools, and specific resources for patients.

- Opioid Use Disorders: Prevention, Detection and Recovery offers a brief overview along with resources in support of opioid use disorder prevention, recognition and assessment, and treatment and recovery.

Application

Determining which patients are appropriate for evaluation is key. The more inclusive the application of the pain management toolkit within a physician’s practice allows for clearer guidelines for staff and improves patient safety. Avoid common misperceptions that short-acting opioids or morphine milliequivalents (MME) less than 90 can be excluded from pain management evaluation because the patient is deemed lower risk. Protocols should be clear and nondiscriminatory, including all patients meeting the criteria for chronic pain.

Barriers to Implementation

Often cited as barriers for not managing chronic pain are the lack of time or familiarity with resources provided, patient behaviors, and increasing scrutiny over controlled substance prescribing. Overcoming these barriers can improve adherence and patient safety.

Lack of Time

Lack of time is commonly cited as a reason for not using validated scales and tools provided in the toolkit. Consider implementing only one tool at a time. If no standardized guidelines are in place in your current practice, start with having each new patient complete a patient agreement. Set a goal to have existing patients complete patient agreement over the next three to six months.

With EHRs creating a system when refills for controlled substances are initiated, physicians are prompted to complete necessary documentation after 90 days have passed from the date of initiation. Training staff to automatically facilitate this process as part of the patient follow-up visit can increase the adoption rate.

With recent updates in E/M coding, physicians can bill for time spent reviewing medical records, previous treatments, and imaging in addition to the time spent with the patient. This allows physicians to be compensated for the extra work and time required to evaluate often medically complex patients.

Review the chronic pain management toolkit and determine what tools best fit your practice setting. Develop a chronic pain management packet for all new patients and existing patients with similar time frames for completion. Review workflows within the clinic setting, introduce during the first visit, complete at next follow-up visit, and schedule additional time for “chronic pain management review.”

The sample packet includes a brief pain inventory, Promis scale v1.2 Global health, ORT, and patient agreement.

Lack of Familiarity with Guidelines/Tools

When implementing any new clinic procedure or protocol, particularly with medically complex patients, resistance is to be expected. One technique that can be helpful to increase the use of validated scales provided in the toolkit is encouraging physicians to take the questionnaires themselves or administer them to a family member. This seems simple, but it works. It can be done quickly and, once familiar with the tools, the physician can determine which ones best suit their individual practice. For example, does this give you the information you need to know about your patient? Will it also increase your familiarity with scoring?

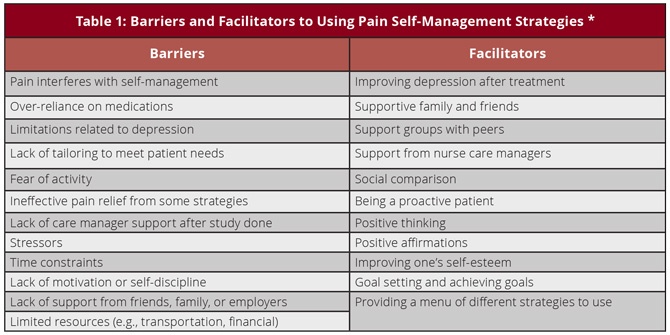

Patient lack of self-management skills is increasingly reported as a source of burnout among physicians providing pain management care. For example, treating underlying depression with a multidimensional approach has shown to increase patient compliance and the ability to engage in nonpharmacologic behaviors to manage pain and reduce reliance on opioid pain medication. Using tools such as a brief pain inventory and global health scales provides insight into the patient’s overall level of function. Using motivational interviewing helps patients set achievable goals.

Safe Prescribing and Monitoring

Nearly 70 percent of drug overdose deaths in 2018 involved opioids, with two-thirds of overdose deaths involving a synthetic opioid (excluding methadone). In addition to the risk of overdose, patients prescribed opioids for chronic pain are at an increased risk for developing an opioid use disorder (OUD). Safer opioid prescribing by physicians and other clinicians is effective at reducing the risk of OUD.

In the 2019 National Survey on Drug Use and Health, 1.4 million persons abused or were dependent on prescription opioid pain medication.

As Deborah Dowell, MD, and colleagues reported in the CDC’s Weekly Morbidity and Mortality Report announcing the guideline for prescribing opioids for chronic pain: “For example, a recent study of patients aged 15–64 years receiving opioids for chronic non-cancer pain and followed for up to 13 years revealed that one in 550 patients died from an opioid-related overdose at a median of 2.6 years from their first opioid prescription, and one in 32 patients who escalated to opioid dosages >200 morphine milligram equivalents (MME) died from an opioid-related overdose.”

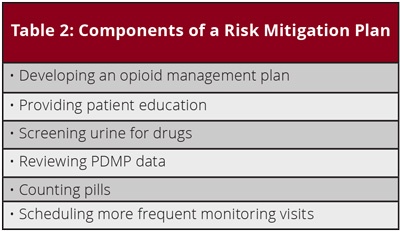

With new guidelines and increased scrutiny, physicians may be hesitant to provide appropriate pain management with opioid medications. Developing a structured protocol for monitoring and compliance in your clinic can set clear expectations for patients and reduce frustrations for staff and physicians. This includes, but is not limited to, written procedures on the frequency of urine drug screens, PMP searches (staff or physician accesses*), medication count protocol, review of an opioid management plan, collaborative information, and taper procedures. Before increasing medication dosages, determine if a functional evaluation has been completed and documented and if this improves function or if this is considered palliative.

(In Washington, a PMP query must be completed before the first refill or renewal of an opioid prescription; at each transition phase; periodically based on the patient’s risk level; and when providing episodic care to a patient who you know to be receiving opioids for chronic pain.)

Identifying Opioid Use Disorder

How does a physician diagnose addiction in the setting of chronic pain?

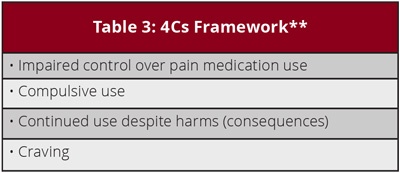

A simplified but practical way to assess for signs of an OUD is the 4Cs framework:

- Identify a patient’s existing or former substance use disorder via clinical interview 4C’s and DSM 5, collateral interview, medical records, and screenings prior to prescribing opioids for pain management.

- Re-evaluate opioid prescriptions after non-fatal overdoses and discuss risks of continued use.

For patients who have a history of substance use disorder, initiating opioid therapy referral to an addiction specialist or reviewing AAFP’s OUD practice manual can be helpful.

These are tools, not a decision. When a patient presents with unexpected results after a urine drug screen or medication count, this should trigger a change in a treatment plan, i.e., more frequent follow-up, additional testing etc., not the discontinuation of care. Patients are more likely to disclose OUD when they know that you can help them. With the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services announcing the waiver exemption on April 27, 2021, family physicians are in a unique position to not only diagnose but treat OUD when it occurs with limited barriers in place. Having a systematic approach can increase patient safety, improve patient compliance, and increase patient and physician satisfaction.

Sources:

- Dowell D, Haegerich TM, Chou R. CDC Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain — United States, 2016. MMWR Recomm Rep 2016;65(No. RR-1):1–49

- Wendy Glauser, Challenges of treating chronic pain contributing to burnout in primary care. CMAJ Jul 2019, 191 (29) E822-E823.

- Jackman RP, Purvis JM, Mallett BS. Chronic nonmalignant pain in primary care. Am Fam Physician. 2008 Nov 15;78(10):1155-62.

- Monitoring Lembke A, Humphreys K, Newmark J. Weighing the Risks and Benefits of Chronic Opioid Therapy. Am Fam Physician. 2016 Jun 15;93(12):982-90.

- Fiona Webster, Kathleen Rice, Joel Katz, Onil Bhattacharyya, Craig Dale, Ross Upshur

An ethnography of chronic pain management in primary care: The social organization of physicians’ work in the midst of the opioid crisis. Published: May 1, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0215148 - Robert N. Jamison, Ph.D., Lisa Gintner, MA, Jacquelyn F. Rogers, RPh, David G. Fairchild, MD, MPH, Disease Management for Chronic Pain: Barriers of Program Implementation With Primary Care Physicians, Pain Medicine, Volume 3, Issue 2, June 2002, Pages 92–101, https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1526-4637.2002.02022.x

- Shaquir Salduker, Eugene Allers, Sudha Bechan, R Eric Hodgson, Fanie Meyer, Helgard Meyer, Johan Smuts, Eileen Vuong, and David Webb Practical approach to a patient with chronic pain of uncertain etiology in primary care

- Upshur CC, Luckmann RS, Savageau JA. Primary care provider concerns about management of chronic pain in community clinic populations. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(6):652-655. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006. 00412.x

- Kaplovitch E, Gomes T, Camacho X, Dhalla IA, Mamdani MM, Juurlink DN. Sex Differences in Dose Escalation and Overdose Death during Chronic Opioid Therapy: A Population-Based Cohort Study. PLoS One. 2015 Aug 20;10(8): e013.

- American Academy of Family Physicians. Opioid prescribing for chronic pain. Accessed January 11,2021 www.aafp.org/family-physician/patient-care/clinical-recommendations/all-clinical-recommendations/opioid-prescribing.html

- Harriet Boxer, Ph.D., and Susan Snyder, MD, “Five Communication Strategies to Promote Self-Management of Chronic Illness” Fam Pract Manag. 2009 Sep-Oct;16(5):12-16.

- Bair MJ, Matthias MS, Nyland KA, et al. Barriers and facilitators to chronic pain self-management: a qualitative study of primary care patients with comorbid musculoskeletal pain and depression. Pain Med. 2009;10(7):1280-1290.

- Washington Medical Commission. “Opioid Prescribing in Washington: What You Need to Know” Accessed June 16, 2021.

Darlene Petersen, MD, is the Medical Director at Rock Run Family Medicine in Roy, UT.

Brian Hunsicker, director of external affairs for the Washington AFP, contributed to this article.