This year, during the Utah State Legislative Session, a bill was proposed, entitled “Physician Practice Amendments.”

This bill is one of those that at first glance — particularly to someone not in healthcare — seems like a reasonable argument. But when you dig deeper and begin to consider the potential ramifications, not just to patients, but also to the practice of medicine as a whole, especially family medicine, it is wholly unacceptable.

This bill would have allowed a healthcare provider to refuse service to anyone based on any religious, ethical, professional or personal reasons. It did not include any exceptions and did not acknowledge the existence of state and/or federally protected classes. In other words, if you had a patient who was part of a religion, in a relationship, or had any other characteristic that you did not agree with, you could simply refuse to treat them with zero repercussions.

These types of “right of conscience” bills have been making their way around the country. Several states have already passed similar legislation.

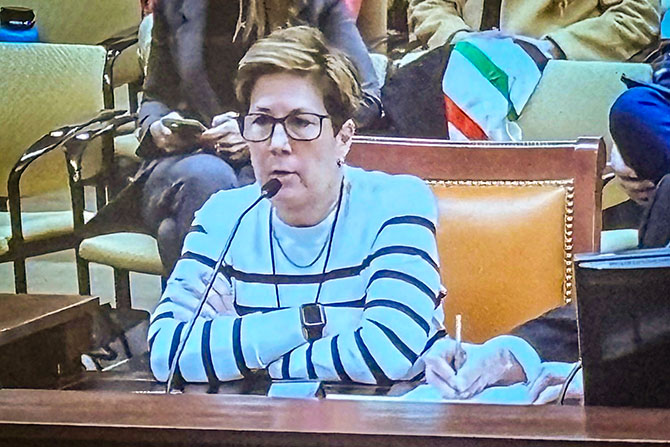

In my seven years as CEO and UAFP lobbyist, this bill created the most uproar among our membership. I fielded more calls on this than in any previous year — all universally opposed.

I love this job — not just for the actual day-to-day, which I enjoy, but for the incredible people I have met. Family physicians are the salt of the earth in healthcare. You care more than any specialty, and your desire for everyone who needs care to receive it is a pillar of family medicine. It is a specialty steeped in empathy and compassion.

Is every patient a perfect fit for your practice and personality? No, of course not. I recently heard a story from a member physician about a patient who refused to actively participate in their own treatment, refused recommended medications and so on. After careful consideration, this physician told the patient that they had realized that perhaps they were not the right physician for them, gave them recommendations for other practitioners that might be a better choice, and they parted ways amicably. Legislators weren’t involved in the discussion, no lawyers needed, they simply found a way forward for both patient and doctor. But if push came to shove, I guarantee the physician would have treated that patient or any other patient if they were truly in need.

Let’s be honest — as family physicians, you will all encounter challenging patients. If there is truly a bad fit — it happens — there are ways to move forward without the need for statutory guidance.

We’ve become a country of “us” and “them,” and this type of law is a dangerous extension of that division. When a physician can decide not to treat someone based on the color of their skin, who they may choose to share their life with, or for that matter, how many tattoos someone has, we’ve lost our way.

I am proud to say I worked hard to kill the bill before it even got a committee hearing and I will continue to fight this sort of “conscience” legislation. As was said by one of the many who contacted me, “I didn’t get into medicine to pick and choose who I helped.”

Note: As of publication date, this bill has been included on the interim study list, meaning the legislature may discuss it again during interim sessions throughout the year. If you have comments or feedback on this, please email me at martindalemm@utahafp.org.